1963, 16 mm, colour, silent, 3 min.

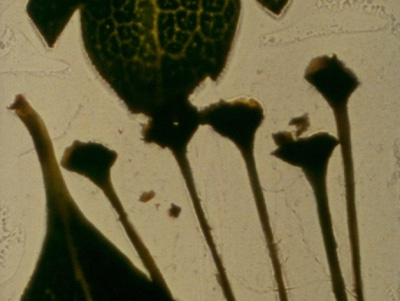

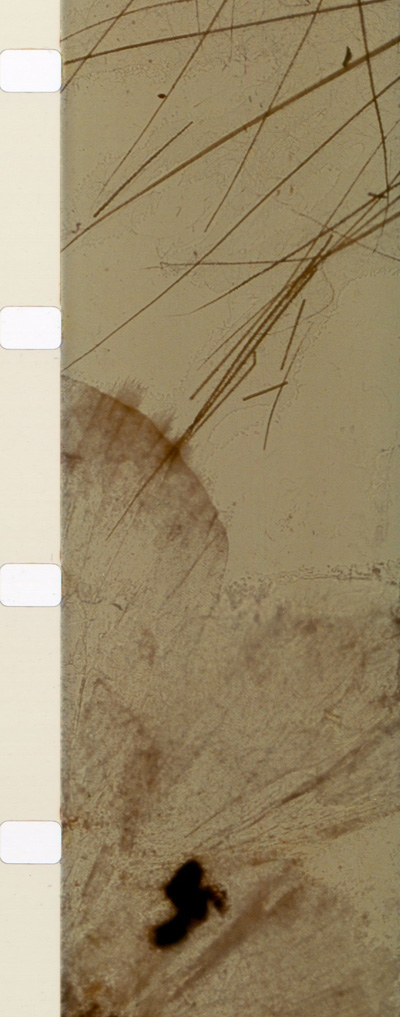

"[Brakhage's] most radical exploration into the inflection of light through his raw materials initially occurred in response to his oppressive economic situation. When he had no money to buy film stock, he conceived the idea of making a film out of natural material through which light could pass... Brakhage collected dead moths, flowers, leaves, and seeds. By placing them between two layers of Mylar editing tape, a transparent, thin strip of 16mm celluloid with sprocket holes and glue on one side, he made Mothlight (1963), 'as a moth might see from birth to death if black were white.'

"The passing of light through, rather than reflecting off, the plants and moth wings reveals a fascinating and sometimes terrifying intricacy of veins and netlike structures, which replaces the sense of depth in the film with an elaborate lateral complexity, flashing by at the extreme speed of almost one natural object to each frame of the three-minute film. The original title of this visual lyric, when the film-maker began to construct it, had been Dead Spring. True to that original but inferior title the film incarnates the sense of the indomitable division between consciousness and nature, which was taking a narrative form at the same time in Brakhage's epic, Dog Star Man.

"The structure of Mothlight, as the film maker observes in a remarkable letter to Robert Kelly printed in "Respond Dance," the final chapter of Metaphors on Vision, is built around three "round-dances" and a coda. Three times the materials of the moths and plants are introduced on the screen, gain speed as if moving into wild flight, and move toward calm and separation; then in the coda a series of bursts of moth wings occurs in diminishing power, interspersed with passages of white (the whole film is fixed in a matrix of whiteness as the wings and flora seldom fill the whole screen). The penultimate burst regains the grandeur of the first in the series, but it is a last gasp, and a single wing, after the longest of the white passages, ends the film."

P. Adams Sitney, Visionary Film

Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1979